RussellDunphy

Churn vs sharedness

At a previous company, I co-led a project to decompose our tangled monolith into well factored modules with clear boundaries.

I want to stress that we didn’t do this on some abstract principle of “single responsibility” or “microservices (or in this case modules) are better”. I’ve seen more crimes against software committed in their name than perhaps anything else except “DRY”. We did it because we faced a real problem.

We had several teams working on the codebase, and some of those teams had different levels of risk tolerance. Some teams were working on parts of the product that were stable, with a customer base that needed reliability. Others were working on parts that had yet to find product market fit, where quick iteration was critical, and bugs getting into production were more tolerated. The problem was that the teams with a higher risk tolerance could break things for the teams with lower risk tolerance.

We needed a way to make this less likely to happen.

The approach we decided on was refactoring the monolith into modules with clear boundaries and ownership in such a way that the “blast radius” of a change was made explicit. Teams moving fast could change their modules safe in the knowledge they were unlikely to break things for teams working on stable parts of the product. Changes to shared modules required a higher level of scrutiny - and communication between the teams affected.

With the approach decided, we needed a way of measuring the success of the project. Ultimately we wanted to reduce the number of incidents caused by one team that affected other teams - but though incidents happened more frequently than we would like, they were rare enough that this was a lagging indicator. We needed something that would give us feedback faster.

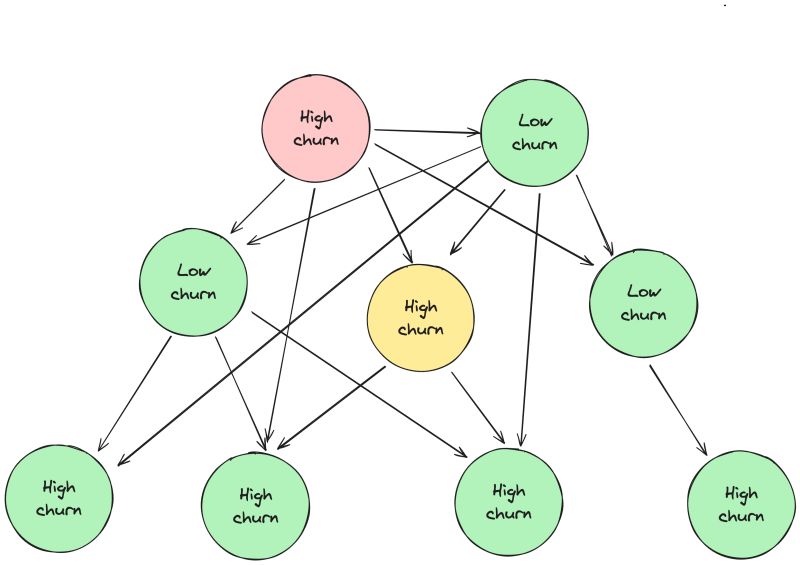

To do this we developed metrics we could track through static analysis of the code. Together they gave us a holistic view of the progress of the migration. One that I found particularly helpful was comparing churn (no. of commits to files in a module over the last 90 days) to how highly shared a module was (no. of modules that were dependent on it):

𝗻𝗼𝗿𝗺𝗮𝗹𝗶𝘀𝗲𝗱(𝗺𝗼𝗱𝘂𝗹𝗲 𝗰𝗵𝘂𝗿𝗻) * 𝗻𝗼𝗿𝗺𝗮𝗹𝗶𝘀𝗲𝗱(𝗻𝗼. 𝗱𝗲𝗽𝗲𝗻𝗱𝗲𝗻𝘁𝘀)

This resulted in a low (good) score for highly shared modules that were stable, which meant we were making fewer risky changes, as well as for frequently changed modules with few or zero dependent modules, which meant we were delivering new features quickly by adding or changing “leaf” nodes - i.e. pages - of the dependency tree. If a highly shared module was seeing frequent changes, we knew we had a problem, and could investigate to figure out why. There are of course exceptions, but overall we found this a useful way of tracking our codebase’s health.